French colonial rule in Cambodia was a complex chapter of subjugation, modernization, and political awakening. For nearly a century, from 1863 to 1953, Cambodia existed under the shadow of French imperialism—experiencing cultural friction, economic change, and a growing thirst for self-determination.

This article explores how Cambodia became a French protectorate, the changes introduced under colonial rule, the resistance it inspired, and the long-term effects that still echo in modern Cambodia.

How Cambodia Became a French Protectorate

In the mid-19th century, Cambodia was a weakened kingdom caught between two powerful neighbors—Siam (Thailand) to the west and Vietnam to the east. Years of conflict, encroachment, and internal instability had left Cambodia vulnerable.

Fearing complete absorption by Siam or Vietnam, King Norodom sought external protection. In 1863, he signed a treaty with France, placing Cambodia under French protection. While this move was initially framed as a strategic alliance, it soon became clear that France sought to dominate, not simply defend.

By 1887, Cambodia was incorporated into the French Union of Indochina, along with Vietnam and Laos. While the monarchy remained, its powers were greatly reduced. Real authority shifted to French colonial administrators based in Phnom Penh and Saigon.

Changes in Cambodian Society Under French Rule

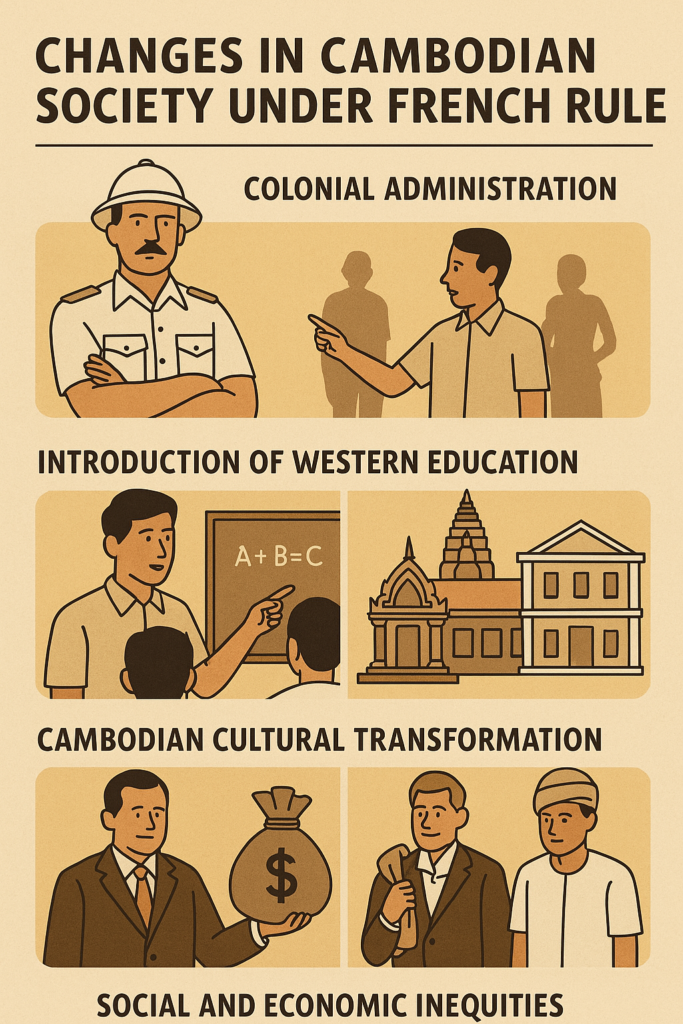

French colonialism introduced radical changes to Cambodia’s traditional society—altering governance, education, religion, and the social hierarchy.

Key societal changes included:

- A centralized bureaucratic administration modeled on French systems

- Introduction of French-style schools, with emphasis on the French language and history

- Marginalization of Buddhist monastic education, which had long been central to Khmer identity

- A colonial elite class of Khmer officials loyal to the French

The royal family remained in place, but under strict control. Buddhist monks were surveilled. Rural peasants—comprising the majority of the population—saw little benefit from colonial rule and were often subjected to land taxes and forced labor.

While a small Cambodian middle class emerged, cultural alienation and economic disparity deepened.

Economic and Infrastructural Developments by the French

One of the most visible legacies of French rule is the infrastructure it left behind. Determined to exploit Indochina’s resources and integrate Cambodia into the colonial economy, the French initiated numerous construction projects.

Notable developments:

- Roads and bridges connecting Phnom Penh with the provinces

- Expansion of the railway system, including the line from Phnom Penh to Battambang

- Establishment of the port at Phnom Penh, facilitating trade along the Mekong

- Urban redesign of Phnom Penh with colonial architecture, wide boulevards, and administrative buildings

- Development of rubber plantations and rice exportation systems

However, these developments primarily served French commercial interests. Profits flowed out of Cambodia, and economic benefits rarely reached rural Khmer communities.

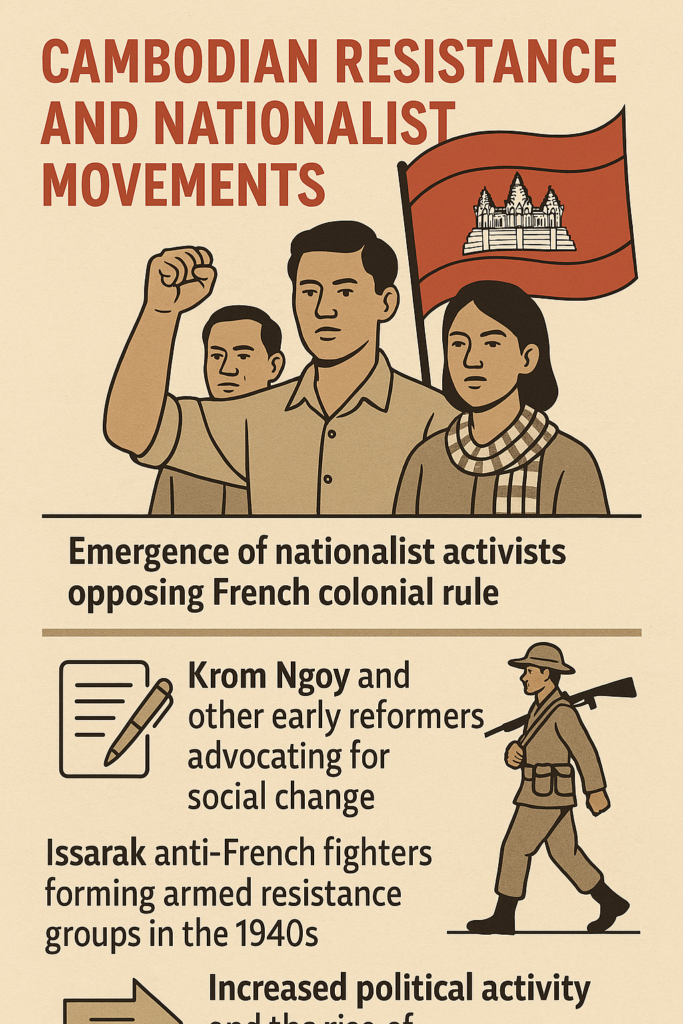

Cambodian Resistance and Nationalist Movements

While early Cambodian society largely accepted French rule as a means of survival, opposition slowly grew—particularly in the 20th century.

Forms of resistance included:

- Rural revolts and peasant uprisings in the early 1900s

- Quiet defiance by Buddhist monks, who resisted cultural erasure

- Growth of Khmer-language newspapers and literature, promoting national pride

- Formation of student associations and political groups influenced by anti-colonial movements in Vietnam and Europe

By the 1930s and 40s, Khmer nationalism had taken root, especially among students educated in Saigon and Paris. Influenced by global anti-colonial ideologies and the weakening of French power during World War II, young Cambodians began to openly challenge colonial authority.

The Khmer Issarak movement, supported by both Thai and Vietnamese nationalists, carried out guerrilla resistance during and after the Japanese occupation of Indochina.

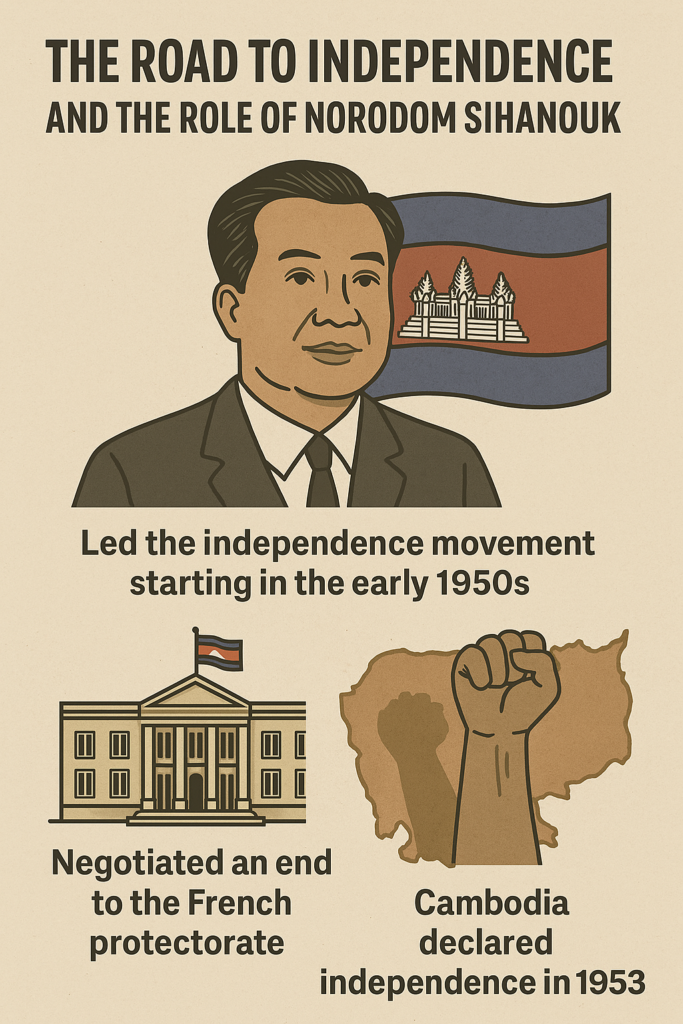

The Road to Independence and the Role of Norodom Sihanouk

In 1941, the French crowned a young and largely unknown prince, Norodom Sihanouk, as king—believing he would be compliant. But Sihanouk would soon surprise them.

After World War II, global pressure to decolonize intensified. Sihanouk began pushing for Cambodian independence, skillfully navigating between diplomacy, media campaigns, and mass mobilization.

In what became known as the “Royal Crusade for Independence”, Sihanouk:

- Traveled abroad to rally support for Cambodia’s sovereignty

- Outmaneuvered French authorities through legal and diplomatic channels

- Galvanized public opinion across Cambodia

His efforts culminated in November 9, 1953, when France officially granted full independence to Cambodia without bloodshed. It was a rare peaceful transition in the age of decolonization and a testament to Sihanouk’s leadership.

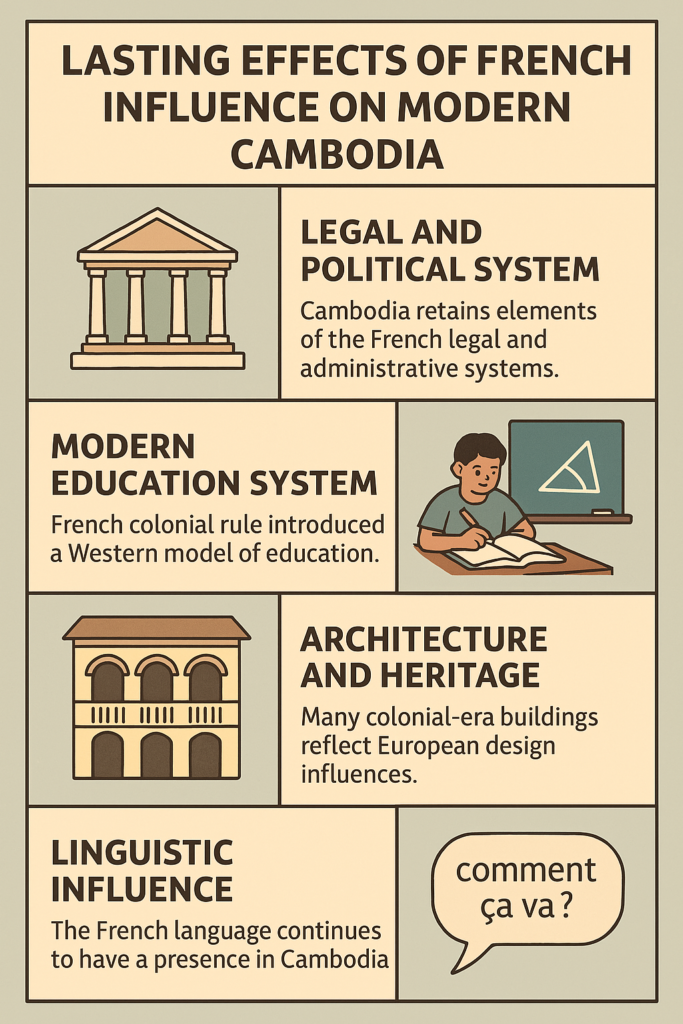

Lasting Effects of French Influence on Modern Cambodia

Though French colonialism ended in the 1950s, its cultural, architectural, and political footprints remain in Cambodia to this day.

Enduring legacies include:

- The French language is still used in diplomacy, law, and education

- Phnom Penh’s colonial architecture, such as the Central Post Office and Phsar Thmei (Central Market), still stands

- French-style education, with French-language schools continuing to operate

- Administrative structures based on French civil service models

- Continued fascination with French cuisine, fashion, and art among the urban elite

However, the darker legacy of colonial exploitation and cultural disruption is also remembered. The period fostered inequality and suppressed Cambodian agency for nearly a century.

Conclusion: From Colonized Kingdom to Independent Nation

The story of French colonial rule in Cambodia is not only a tale of domination—it is also one of survival, transformation, and triumph. The Khmer people endured foreign control, absorbed modern ideas, and ultimately reclaimed their destiny.

While colonial rule reshaped Cambodian society, it also gave rise to the very forces that would lead to independence: a new class of educated nationalists, a sense of modern nationhood, and a resilient royal figure in Norodom Sihanouk.

Today, Cambodia continues to evolve—mindful of its colonial past, proud of its sovereignty, and determined to preserve the cultural soul that colonialism could never erase.